Design threads_

A collaborative Report Unraveling the state of design today_

Thread_

(NOUN)_

1. a theme or characteristic, typically forming one of several._

2. a connected group of pieces of writing on the internet, where people talk about a particular subject._

INTRO

The state of design is impossible to define, and this report doesn’t come close. Instead, this project brings together a series of threads—interwoven questions, themes, provocations, and shared feelings—that emerged from conversations and research with and for the design community. Some are expected, others unpredictable, all evocative of what it means to be a designer today.

What is good design? Who gets to decide? How are designers feeling right now? Are we tasked with too much? Are we doing enough? How is our role changing? Where does design go from here?

Design Threads isn’t the answer to these questions, but an invitation to start unraveling them together — pull out a thread, see where it takes you, and leave one of your own.

This project is a collaborative, non-commercial initiative from PORTO ROCHA1 and Float2. It would not be possible without the who participated in this research, through 1-on-1 conversations and an open survey. All participants’ quotes are kept anonymous within the report itself.

1. PORTO ROCHA

Is a New York-based design and branding agency developing creative and strategic work that engages deeply with the world we live in.

2. FLOAT

Is a strategy and cultural analysis hub that combines innovation and research methodologies to uncover the cultural shifts that matter the most. things happen; people change; get the vibes.

Supported by Wix Playground

Developed by Bloquo

APPROACH

EVERYONE’S INVITED

While this report centers on topics relevant to visual design, you don’t have to be a designer to read it. These threads began as a collaborative effort between designers, strategists, and creatives, for the design community and beyond.

BLESS THE MESS

It’s part of the process. Our goal isn’t to resolve contradictions, but to use them as a tool that can uncover the realities of the world we’re living—and designing—in.

KEEP QUESTIONS ALIVE

Our work doesn’t end here. Each thread ends with more questions, not answers. Join in, push back, pass on (or don’t).

METHOD

The content of this site is the result of interviews with 30 emerging and established design professionals from different areas of design (primarily graphic, 3D, art direction, web design, branding & advertising, among others), and 250 responses from the design community gathered through an open and anonymous online survey.

Participants

LIMITATIONS

Of course, this sample does not represent the entirety nor plurality of the global design community. Though we attempted to include as many perspectives as possible within the limited scope of this project, we want to be transparent about the limitations of our sample.

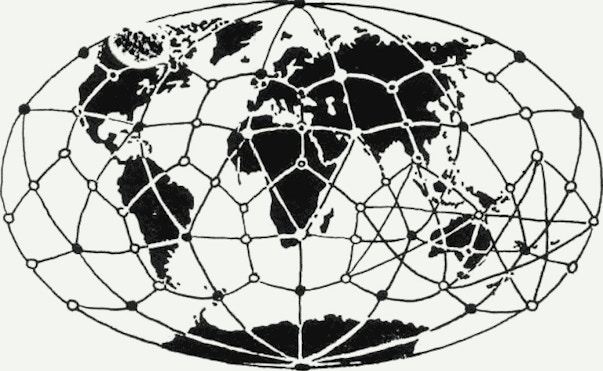

Although designers from 32 countries and 77 different cities took part in this research, the majority of our respondents are from the United States and Brazil. However, we believe design happens everywhere—not only in the design capitals of the world.

It’s important to acknowledge that to be a professional designer is often a position of privilege. Though the design world is becoming more inclusive and accessible, we have a long way to go. We acknowledge that our sample could reflect some of the historic inequalities of the profession, even as we strive to change them.

Taste isn’t innocent. While taste may seem subjective and individual — one person’s trash is another’s treasure — it also reflects existing hierarchies of power. Operating within an increasingly global and connected world, designers are challenging long-established definitions of how design looks and behaves. How do we define “good” and “bad” design? How do we unlearn the Western tradition as the only way? How can we promote inclusion in a system that excludes so many? In a field that claims to be forward-thinking, designers are interrogating the rules of taste and calling out structural inequalities that can no longer be ignored.

1.1

Taste Reflects Power

“If we are makers of taste or visual

culture, who is deciding what is good? And

why those people?”

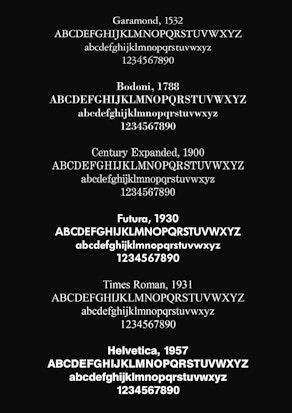

Consciously or not, design movements from Europe are still a primary framework through which we evaluate design around us. This predominantly white, Western perspective perhaps has the most power in university classrooms and curricula across the globe, where the few students who come from less privileged backgrounds often feel unrepresented and excluded.

WHOSE TASTE MATTERS? DESIGN THREADS EXHIBITION

FIGHT FOR THE UGLINESS, @SCREENSAVIORS

“A good design can be straightforward, very clean. But it can also be something that is supposed to make you feel cramped and a little uncomfortable, but also curious.”

“A lot of designers’ work falls on the lines of a Swiss grid system, using that as a base and a starting point. Then we like to break it, we like to make it our own, we have to add our own perspective and spice, if you will. But honestly, if you went to design school in the Western world, we probably have the same base. And I think it's challenging because there are other [non-western] design movements and perspectives that are interesting.”

“Sometimes I have to catch myself when I’m looking at something and saying, ‘that's horrible’. Well, why do I think that's horrible? Is it because aligning myself to a set of values that are outdated? If I think Swiss design is the ultimate design, I’m not questioning that notion of what I've been told is good design. So even if I don't immediately like something, I sort of try to look for redeeming qualities in it.”

1.2

Going Global

“We don’t idealize or glorify specific

people or movements as much anymore.

There’s not a single voice that is the

right one.”

GOOD-DESIGN-AT-WORK

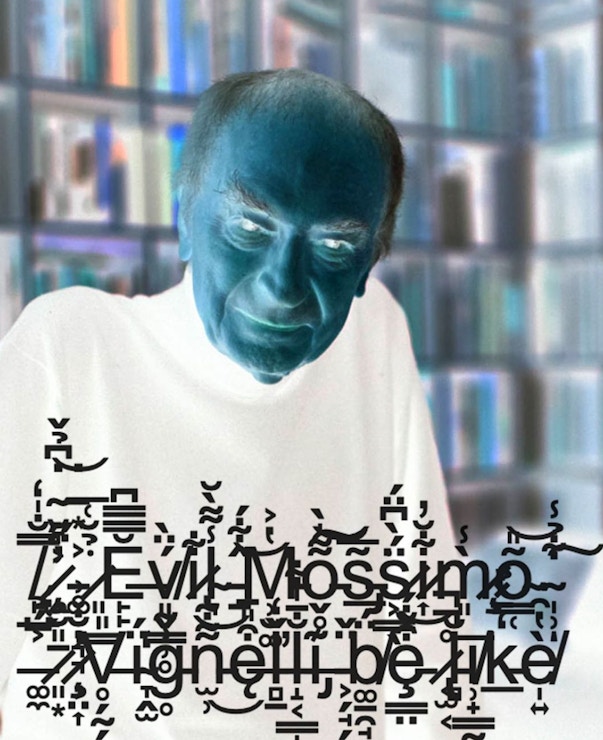

singular genius:

“When I was in college, there was ‘the designer as a superstar.’ There was a spotlight on them and they are almost at celebrity level. But because of how accessible information is and how many different people have access to it, the star thing isn’t as relevant. There’s so many designers out there, we don’t have just one star anymore.”

“Generally, Western practices of knowledge-making are so obsessed with ‘you are the one that did this’, ‘you are the one with the answers.’ It's entirely antithetical to the reality of literally any form of knowledge production, since there's no one individual person who knows the shit. [Instead] it's the community and context in which they exist, the lineage of thought, the people who’ve brought them there that are the ones co-creating the knowledge.”

“This idea of the designer as the author and singular voice is changing. I think all of us have worked in studios named after someone, ‘Mr. Studio.’ And I think this has luckily changed a bit. There are a lot of people involved in a project and I think including everybody who has contributed is super important. [...] What we can really do is credit people and elevate each other.”

“I’m frustrated with the institutions of the game, you know, the old gatekeepers of design who have retired from advertising. [...] What are alternative ways of practicing that don't rely on a head of a studio, taking on clients and just extracting value from young people?”

from the universal:

“The question about who designs and for whom is something that is already happening. And I will say positionality is very important right now. Which point of view are you speaking from? You have to position yourself, understanding that there is not just one [right] choice, there will be different ones.”

“With more voices, what good design means is changing rapidly. I think that's a really incredible thing that's happening right now. ”

“Today I think design has become less universal and more personal. We care more about personal taste or interest, and it's more and more divided and plural.”

"Growing up in Brazil, I looked up to design figures outside of my own environment as the ones to follow, glorifying European and American designers and undermining my own roots. Ironically I ended up moving to New York and that notion was completely shattered. I quickly realized I had more to offer them than the other way around."

1.3

Deconstruct the system

“How do we meaningfully intervene to

change broken systems?”

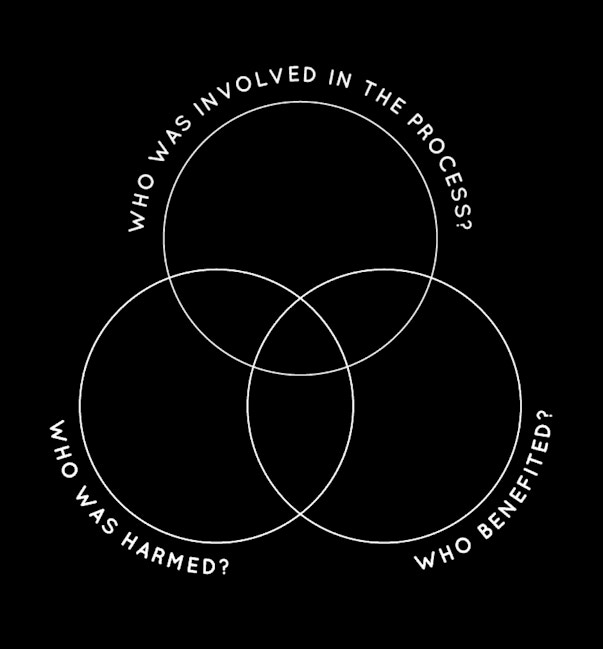

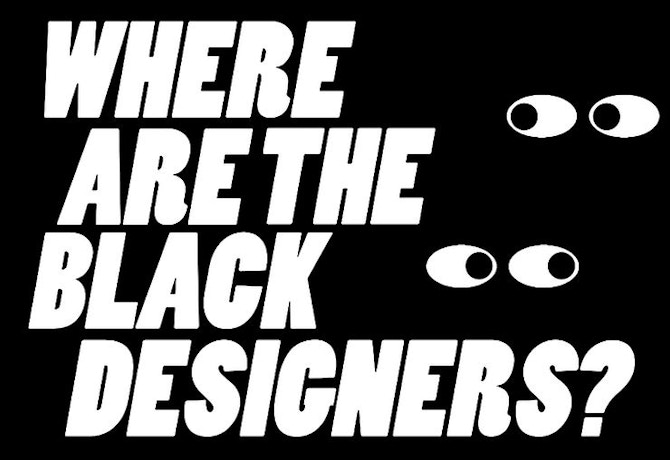

The question posed in 2015 by Maurice Cherry (and others) remains urgent seven years later: “Where are the Black designers?” And with it comes further questioning of who has been and is still excluded from the field, particularly in leadership positions. Where are the Indigenous designers? The AAPI designers? The Latinx designers? The disabled designers? The women, nonbinary, trans, and queer designers? The list goes on.

"Where Are The Black Designers?", 2015 SXSW, Maurice Cherry, Revision Path

While some respondents see shifts toward inclusivity in design, many pointed to the potential pitfalls and contradictions of that process as it unfolds under capitalism.

capitalism:

“I think the industry has become more inclusive than it used to be. We've maybe created more diversity, but still less than 10% of all designers are Black, at least in the New York scene. So I think too much pride can keep us from making additional progress. ”

“I don't think design will ever be actually inclusive. Because, well, capitalism will never be inclusive! We're operating under it, so it has become more inclusive, but in a way that’s motivated by profit.”

“Literally how do I work in a field that’s origins are explicitly related to propping up capitalism and supporting colonialist ideals?”

“If you're interested in, for example, bringing people into design who are not more people from rich backgrounds, you have to change, for example, your system of grants, and scholarships; then your system of work, economy, and so forth. There are many levels.”

“Change doesn't happen overnight. But we can promote change through relationship building, maybe building capacity, building networks, building collective knowledge, collective understanding around a particular topic as we attempt to negotiate it. ”

“We have to think about what inclusion actually is, and if inclusion, as we are seeing it today, may not allow for real change inside the organization. Sometimes we see inclusive spaces, where the people who make the decisions are the same people [who’ve been in power], and they’re just changing the composition of the people around them a bit. We need to give people the possibility to create a new way to organize.”

UNRAVEL

1. How do our tastes and definitions of “good design” reflect what we were taught?

2. Whose ideologies have we followed and whose might we have excluded?

3. How can we help to make practices of inclusion institutions and agencies more materially beneficial for the global majority of designers, rather than the image of an institution/company?

4. What is designers’ responsibility in calling out agency leadership to make changes? And can we go beyond that?