“I like that melting face emoji. Why? Because it feels like it's smiling but not super happy. It's melting and there's nothing it can do. It’s kind of content with the situation, but it's melting. Lol.”

“Maybe the ‘spiral eyes’. That's the one I resonate with the most. It’s overwhelmed but not necessarily with bad stuff, it’s just, you know… too much. It's everything on high volume.”

“[The spiral emoji], an infinite digital archive that one can scroll through chronologically back to the beginning of design, but one never actually reaches the beginning because there's so much that has been created even in the last 100 years.”

2.1

Stuck in Lightspeed

“Everything’s moving way too fast; when do

designers get to pause and reflect?”

“The increasingly fast-paced and high turnover of trends in culture and design means designers are always trying to keep up with clients who are always chasing the latest.”

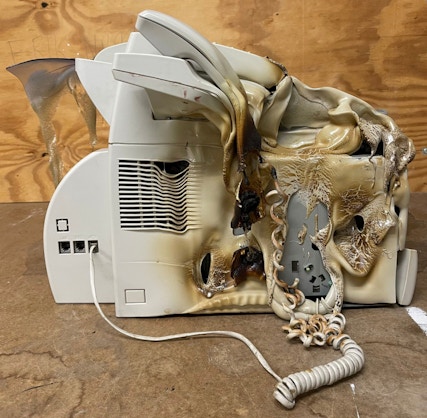

“We just go really fast, design is just so fast-paced. And we're constantly just making, and making. The mind is a muscle that we keep on, so it does get tight. I feel like designers need some rest in order to give you the chance to have great new ideas. you can also get burnt out creatively.”

“How do we stay thoughtful and not churn stuff out just to churn stuff out? How can we not fall under the pressure of the speed of our capitalist society and fight for slow and thoughtful work?”

“There's a lot of design that's just visually provocative, but it's really missing all of this substance. I think of it like junk food. There's never been so much junk food in the design world. And so there's just a lot of people who don't know any better, they see that and they think that's good work.”

2.2

Sea of Sameness

“It’s a really great looking pointless bag

of glitter and garbage.”

What object best represents design in 2022? One response: “The photocopier.”

“Everything looks the same. Trends get tired very quickly. And when something finally looks different, it gets bullied into the ground.”

“[Right now] everybody's trying to please everyone else, and you end up with a lot of stuff that looks the same.”

2.3

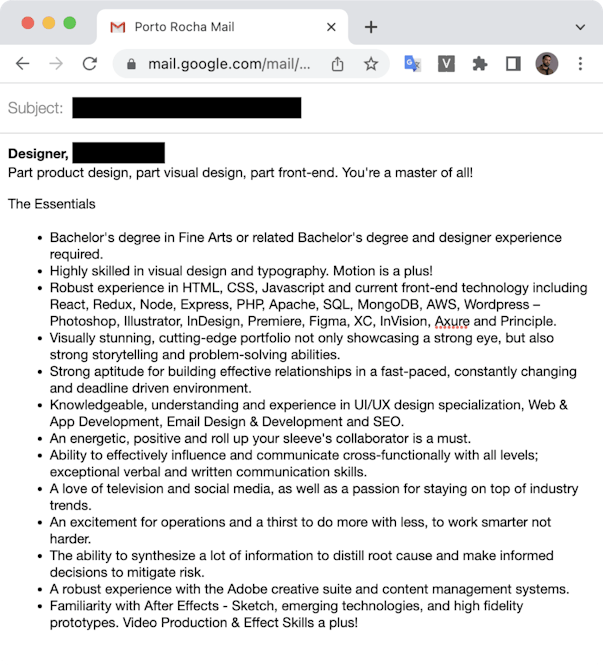

Multi-hyphenates Anonymous

“Like a clown with three balls, we deal with a lot

of things all the time. And we try to manage

everything, to not fall apart.”

JUGGLER EMOJI, APPLE

DESIGNER POSITION JOB DESCRIPTION FOR MEDIA COMPANY

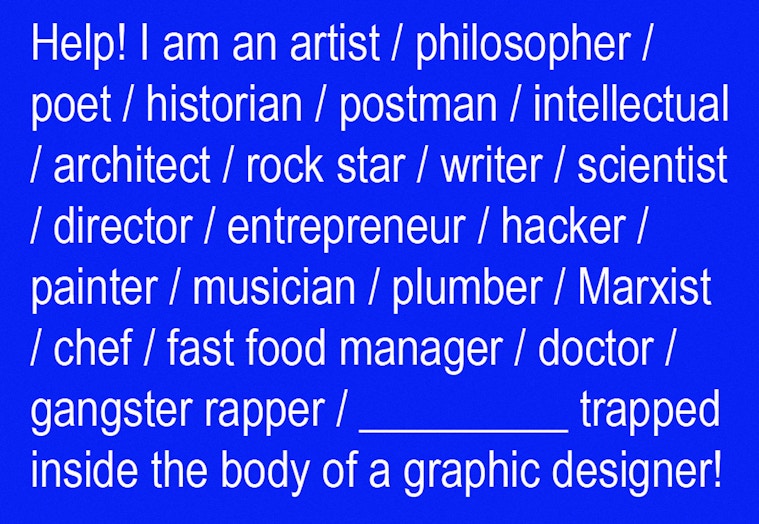

“Today, designers are multi-hyphenates. I think designers are expected to be content creators, strategists, expected to be a lot of things. I think there is a lot more pressure on designers now.”

“[Designers are] living in a world with insurmountable tasks of brain power and deliverables paired with impossible deadlines.”

“I don’t want to have to know every software and skill. I just want to be a graphic designer — not motion designer, 3D artist, UX strategist.”

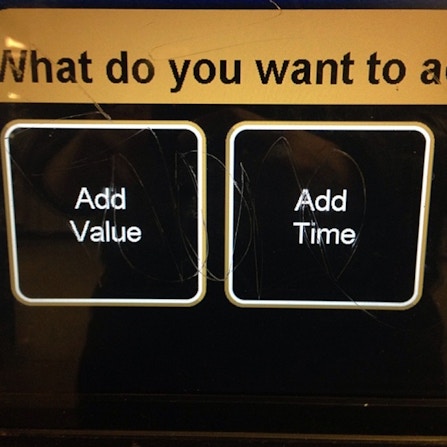

“Technology is great because now I’m working from home and closer to my family and that’s amazing. But I feel like I'm working now more than ever though. It's like not leaving my office at all. There's no nine to five, it's just like nine to twelve.”

“I would ask if design is a practice that calls for urgency at all. Does a sense of urgency come from the engine of capitalism demanding workers be faster/better? What would it look like if the field prioritized slowness and thoughtfulness rather than arbitrary deadlines set by non-creatives?”

“Designers don't have one organization that helps to regulate labor. We’re just kind of talking to each other and trying to organize ourselves. I think it creates some problems and I hear a lot of people complaining about the current state of design. Maybe they're not always talking about wages or health care, but those are big problems. [...] In a way, we see also burnout, depression, ADHD, because of all those things.”

“I think designers would benefit immensely from a union. I think about some of these big studios where there really was no collective bargaining power. Working at having experience working at a big studio felt like you couldn't demand anything because they could fire you and there was a line out the door. so there was really no way to advocate for yourself. I've had experiences staying way past what was considered my working hour without overtime compensation.”

UNRAVEL

1. How has the abundance and speed of information influenced our working habits?

2. How do we break away from the moodboard effect in how we research?

3. Can designers advocate for the right to rest without sacrificing financial stability?

4. How important is personal fulfillment in a professional job?

LINKS

"how to do nothing"

Jenny Odell

Typelab Noise: A Mental-Health First Approach to Creative Advice and Discussion

“In Defense of the Poor Image”

Hito Steyerl

Graphic Support Group Podcast

The Hmm: An inclusive platform for internet cultures

“The Age of Algorithmic Anxiety”

Kyle Chayka

On BLACK MEME (Forthcoming)

Legacy Russell

24/7: Late Capitalism and the End of Sleep

Jonathan Crary